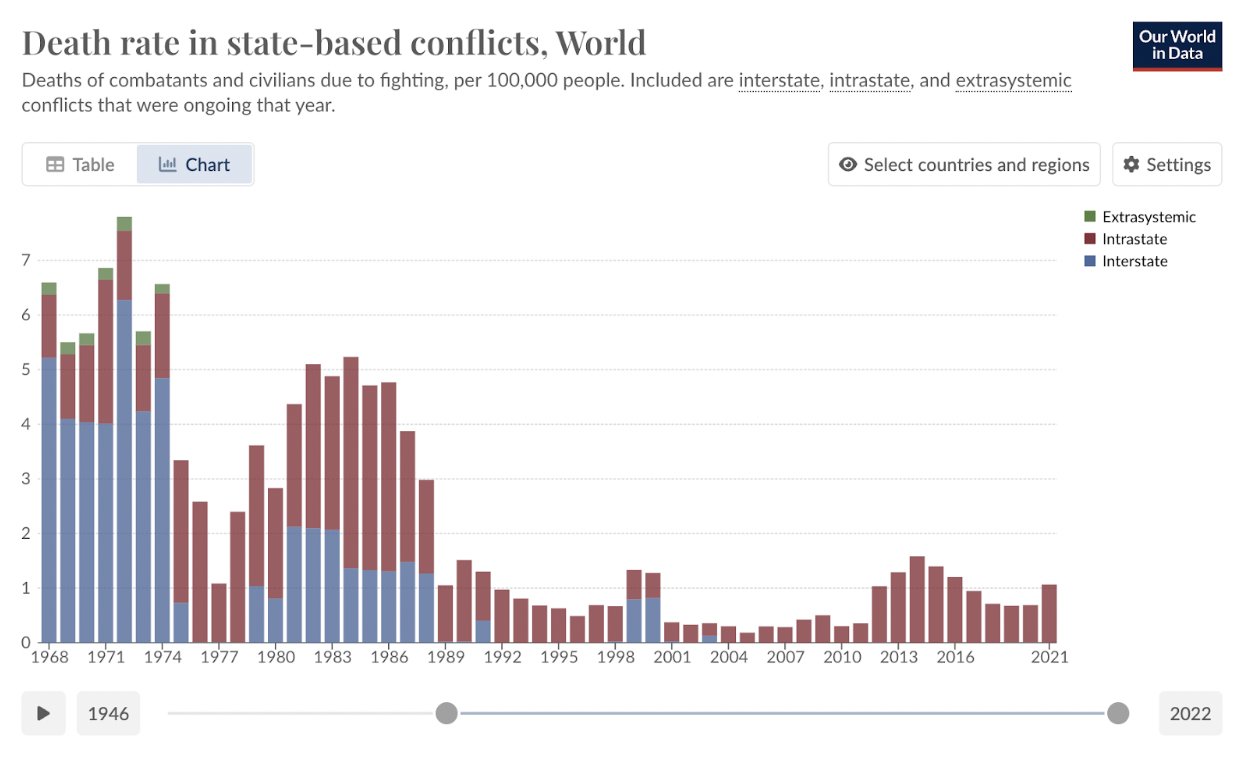

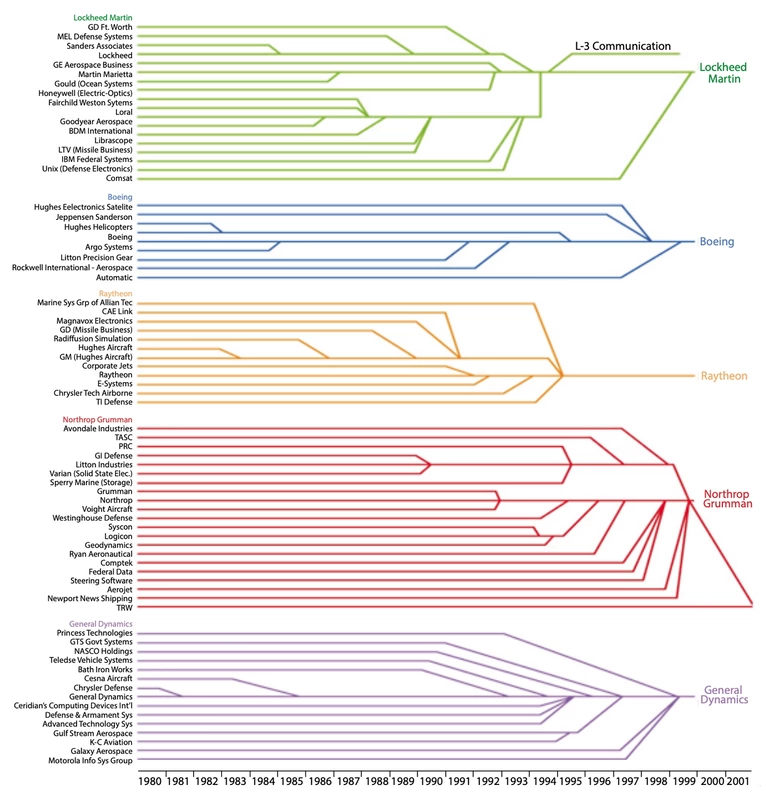

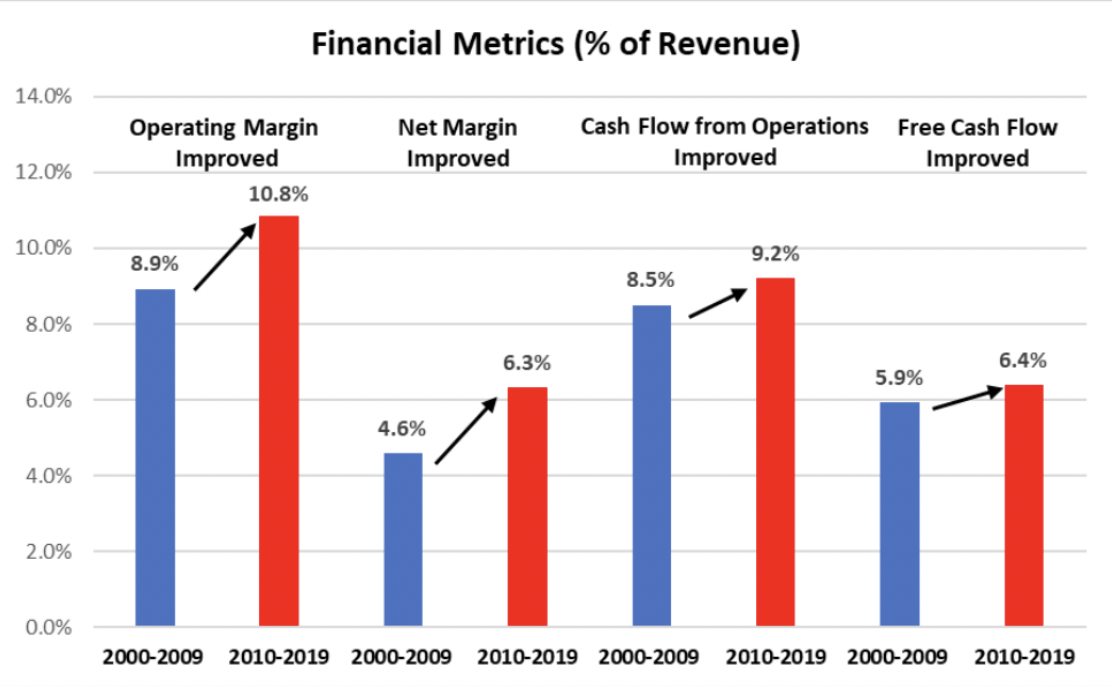

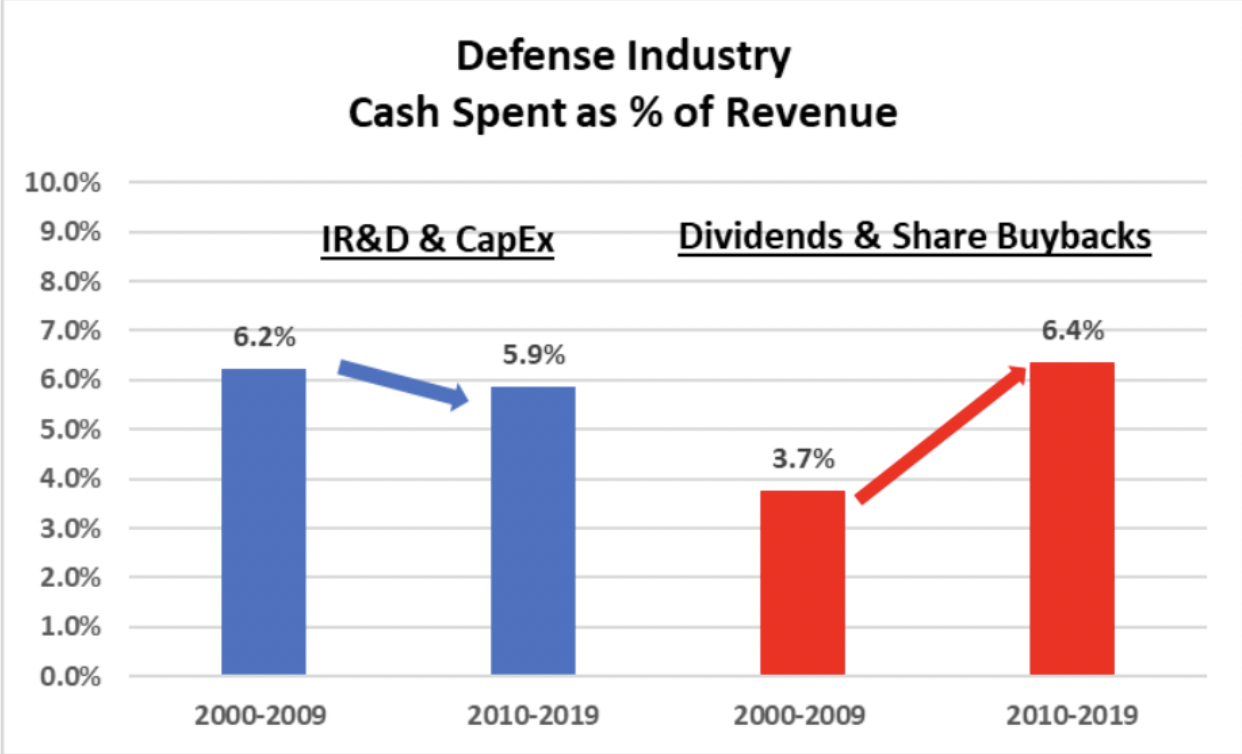

A Shifting World Order When the Cold War ended, the world entered a unique period of history: the so-called “Pax Americana”, in which the United States was the world’s sole global superpower and took on the role of policing the world. With some notable exceptions, American interests overseas often quelled violence, as peace led to easier trade and the U.S. could project power with currency instead of weaponry. Just take a look at the sharp drop in all forms of violent conflict following the dissolution of the USSR, and you’ll find that the past few decades have been the most peaceful period of modern history. This period of world history is over. 2022 was the deadliest year in armed conflict in almost two decades. Casualties in Ukraine account for much of this, but this trend isn’t exclusive to the Russian sphere of influence. In 2023, the violence continued: as Ukraine kept bleeding, civil war broke out in Sudan, and the Palestinian conflict triggered proxy fights across the Middle East that threaten to throw the whole region into chaos. The ripple effects from these major-power conflicts are showing up across the globe, with regional tensions turning hot everywhere from Armenia to Niger to Myanmar to Ethiopia. According to the ACLED, conflict is at its highest level since the index began in 1946, with a 22% increase over 5 years leading to the horrifying statistic that in 2023, one in every six people was exposed to armed conflict. The Peace Research Institute Oslo came to similar conclusions, finding in June of 2023 that political violence was at a 28-year high. So far, 2024 shows no signs of stopping the swarm of conflict. Haiti ended a long downward trajectory with a collapse into a failed state with armed gangs now controlling the majority of the embittered island nation. Peaceful resolutions have occurred in none of the aforementioned conflicts, and dramatic failures with Israel and Haiti make the UN look like an increasingly useless tool for mediation. And lest we forget, against this chaotic backdrop, Chinese institutions are inching ever closer to military action against Taiwan—an act which the U.S. has vowed to defend against. There are nuances to each conflict, but the general pattern from Asia to Europe to the Middle East is clear: American influence is not enough to deter conflict anymore. Without the power of intimidation on their side anymore, it’s all but certain that the coming decades will bring forth enemies that are both willing and empowered to test American and American-allied military might whenever they see an opportunity to. That leaves the U.S. with a pressing question: Can it pass these coming tests? Monopoly Effects on Defense Market Dynamics Historically, the U.S. passes these tests with flying colors, winning both world wars and besting the USSR in the largest security competition in history. In the relatively peaceful years since, serious structural alterations to the defense industry have occurred, opening questions about its efficacy in times of war. The rise of institutional finance dramatically changed the composition of the entire American economy, and the defense industry was not immune to such shocks. In the wake of financial deregulation that allowed firms to play with more and more leveraged capital, Wall Street realized it now had the weight to reshape entire industries through mergers and acquisitions (M&A). To this end, financial firms started to make easy profits by rolling up a bunch of smaller competing companies into big conglomerates, giving them more pricing power and leverage in negotiations. Taken to its extreme, M&A can result in super-firms that control entire industries, commonly known as monopolies. Monopoly power is the ultimate threat to the success of a free market system—and this key vulnerability is already wreaking havoc on American security capabilities. To see this in action, let’s examine the cases of Booz Allen, Olin, and Vista Outdoor. The NSA is the agency responsible for making the government’s online operations safe from cyberattacks. Its prime contractor for this mission is Booz Allen, which is famous for using monopolistic price-fixing tactics in other areas where they hold government contracts. For the privilege of the contract, Booz faced competition from a company called EverWatch, which developed a more efficient way of delivering security services. When a new NSA contract was up for grabs, Booz and EverWatch were the two contractors up for the bid. Rather than competing for the contract by making a better product, Booz decided to simply buy EverWatch. Perhaps unsurprisingly, EverWatch itself was the product of four mergers and seven acquisitions, meaning the Booz acquisition was the final step of a long roll-up chain of security contractors for the NSA into a single monopoly. The DOJ sued to stop the merger—blatant monopolies are illegal, after all—but antitrust lawsuits are notoriously slow with low success rates. With no competition for the bid, Booz had no incentive to make better security services. The government was left overpaying for a lower-quality service, simply because a series of mergers and acquisitions left them with no other option. A year later, Russia hacked into hundreds of federal agencies. Ammunition is another area where M&A has fundamentally changed the market dynamics. In 1995, before the M&A spree, the U.S. defense sector made 837,000 rounds a month. Today, production capacity is 30x smaller than that. This low production isn’t from a lack of demand; in fact, ammunition demand hit all-time highs in 2012 and stayed high throughout the 2010s. Despite this, production capacity today is lackluster, suggesting corrupted market dynamics due to monopoly power. Despite the outward appearance of a competitive market, all ammunition companies in America, including famed centuries-old brands such as Winchester and Remington, are all owned by just two companies: Olin and Vista Outdoor. Just like with the NSA contracts, these monopolies were engineered through a series of M&A deals. Remington, for example, was purchased from bankruptcy by Vista Outdoor after private equity giant Cerberus Capital bought it, extracted its cash, and left it saddled with debt. Remington thus completed Vista Outdoor’s rollup of the ammo industry, which also included direct or chain acquisitions of Federal Premium, Omark, CCI, and Speer Bullets. Winchester was added to the portfolio of the Olin Corporation, a chemical company. The fact their main business model has nothing to do with ammunition was no bother to Olin, who is the current holder of a $30 million DoD contract and produces a whopping 85% of the government’s small-caliber ammo. Now, the US is left with just 14 operating ammunition plants, down from the peak of 84, and has only two companies to turn to in the face of heightened need for ammunition. With a lack of competition, there are no incentives for ammunition production to be ramped up, and even if it could be, the ability to collude and price-gouge would mean detrimental per-unit costs to the taxpayer. Unprosecuted monopolization is permeating throughout the defense industry. Booz Allen, Olin, and Vista Outdoor are only a fraction of the contractors with dramatic failures in critical areas; do we even need to mention how aggressively bad Boeing’s products have become? All around us, the defense base is cracking under the pressure of monopolistic pricing power, leaving the state of American war readiness up in the air. Come On, Is It Really That Bad? In 2022, America spent $877 billion on defense. That’s 40% of the entire world’s defense spending, and three times more than any other single country. Even an inefficient allocation of that vast amount of resources would still allow the U.S. to successfully arm itself and its allies, right? Wrong. Defense spending is only a relevant statistic if that spending actually buys things. With so many monopolies entrenched in the defense base, taxpayer money is often unable to buy things; it’s routine for even basic items to be overcharged by 4000%. When accounting for purchasing power parity (which measures spending power, or “bang for your buck”), America is almost outspent by China—a far cry from the theoretical tripling of resources that the pure spending measurement indicates. Up and down the value chain, entrenched monopolistic practices in the defense system have left the American military incapable of fulfilling a variety of basic military needs. As a result of the ammunition industry consolidation, top NATO officials and President Biden are warning of a coming shortage, which is already affecting the domestic market as suppliers race to try to feed government demand. Leaked intelligence documents echoed widespread warnings about the dire state of American naval shipbuilding, which produces just 1/200th of the ships that the Chinese navy does, and the ships the Navy can produce are consistently bogged down with multi-year delays. The Pentagon has admitted that it can’t make enough rockets or ball bearings to keep the military sufficiently supplied, and the same goes for Stinger missiles, which have a five-year replacement timeline. All of this is on top of other existential issues the U.S. faces, such as the fact that China controls 95% of the world’s rare earth metals, leading the Department of the Interior to assert that America is 100% reliant on foreign adversaries for the metals that make up their weapons of war. So, yes, the military-industrial complex is in really bad shape. Or, as leading security think tank CSIS put it in March of 2024, “Overall, the U.S. defense industrial ecosystem lacks the capacity, responsiveness, flexibility, and surge capability to meet the U.S. military’s production and warfighting needs.” In a new world flush with threats from every corner, America needs to be able to engage in conflict anywhere in the world while deterring or fighting China simultaneously. That is, to put it lightly, a tough task for a nation that is already low on ammo, ships, planes, ball bearings, and missiles, not to mention the fact that none of those can be made at all without reliance on foreign materials that are monopolized by its greatest adversary. The Cartel The defense sector is failing in quality and quantity across a number of unrelated goals (ammunition, cybersecurity, missile production, etc.), which is a textbook sign of a systemic problem. To examine monopolization as the systemic issue, let’s get away from examples and statistics and zoom out to take a look at the U.S. defense base as a whole. Perhaps there is no greater explanation of the structural alteration than this simple visualization of defense M&A activity, put together by the Commission on the Future of the US Aerospace Industry. It’s no coincidence that in the 1980s, when American military might was at its peak, there were dozens of prime defense contractors. Now there are just five, and production capacity is in shambles. The prefix mono implies that monopolies can only be one company, and therefore in a market such as the one depicted above, there are no problems, since five companies compete with each other. This could not be further from the truth. Despite the existence of five different prime contractors or two different ammunition producers, the reality of the situation is that their interests are aligned, leading them to act as one. This is the process of cartelization, which is illegal in the U.S. and most countries worldwide. Yet, our very own defense industry has become a cartel, and has used that artificially created monopoly power to extract taxpayer cash at the expense of national security. Almost as soon as the “big five” became entrenched through M&A, lots of typical cartel behavior emerged. In 2000, defense lobbyists eliminated the “paid cost” rule, which dictated that contractors needed to pay supplier invoices before billing the government. This is important because subcontractors are the ones who actually build and make most of the things the military needs; eliminating paid cost means that prime contractors are allowed to pay them late and hold the value of the contract over their heads as leverage, which leads to more failures, more consolidation, and less money to reinvest into research and development. However, the paid cost issue is more important as proof of cartel behavior. This lobbying effort wasn’t a competition between a prime contractor and another prime contractor to give the government better goods or lower prices, it was a coordinated effort to enrich all of the prime contractors at the expense of everyone else—the textbook definition of a cartel. Over the decades, more typical cartel behavior followed. The industry’s profits were soaring since eliminating competition meant they had total control when negotiating prices with the government. Also, with no competition, these profits no longer had to be spent on R&D to make better goods, so they were immediately diverted to enriching executives via stock buybacks, as shown in this excerpt from a Pentagon report on the defense industry. All of this has resulted in sector-wide failures to produce goods and services critical to U.S. defense. Properly functioning markets rely on competitiveness; by allowing a cartel to monopolize the defense industry, America has eliminated the most important element of a functioning private-led defense base.

Conclusion The American military-industrial complex is a shell of its former self. Plagued by decades of financial engineering, American defense contractors have prioritized stock prices over war readiness for too long, and the cracks are beginning to show. At the heart of the issue lie the prime contractors, who have formed a monopolistic cartel that accrues billions in profits (of taxpayer dollars!) while routinely failing to meet the government’s defense needs. Breaking up the prime contractors, reverting the contracting structure to reflect pre-1990 regulations, and encouraging the development of adequate competition in every sector of the defense industry are the first steps to being a competitive military in the 21st century–and with a serious competitor arising for the first time in decades, the clock is ticking for America to break free from its monopolistic shackles. Jack is a senior at the University of Washington studying economics and entrepreneurship.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|